|

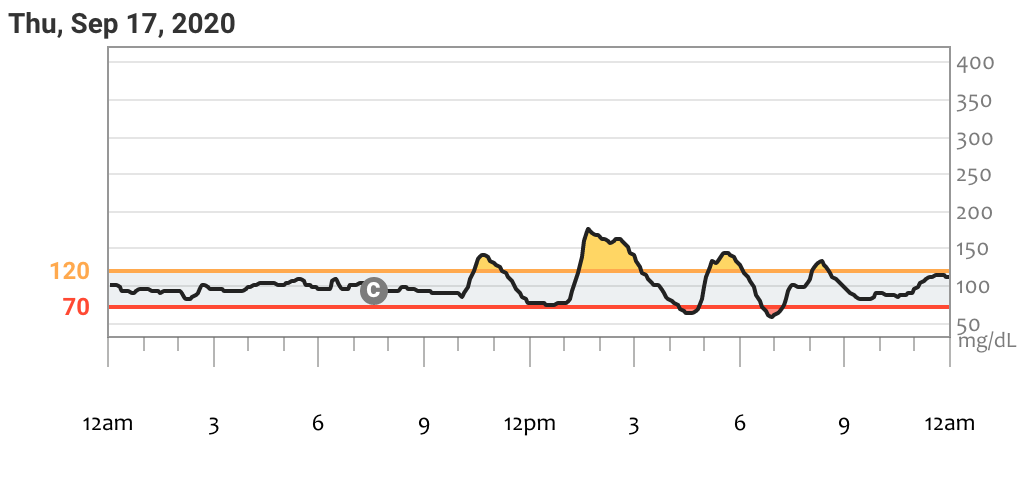

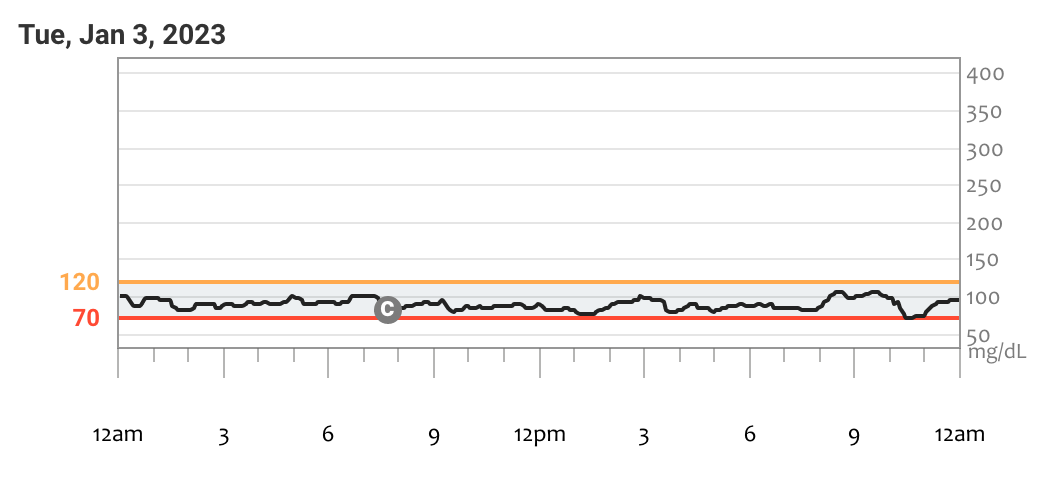

After years of struggling with chronic – and dangerous – reactive hypoglycemia, I finally tried the keto diet and it’s changed my life forever. Reducing dietary carbohydrates to resolve chronic low blood sugar may seem counter-intuitive, but for people with dysregulated insulin production or insulin resistance, low-carbohydrate diets like the ketogenic diet may be the most effective choice for preventing hypoglycemic attacks. I struggled with chronic reactive hypoglycemia (low blood sugar after meals) for years until I started the keto diet in 2020. This change has been transformative for me and many others struggling with unstable blood sugar. In this article, I explain the science of why post-meal hypoglycemia occurs, what steps I’ve taken to prevent it from happening, and how I’ve made a ketogenic diet a sustainable choice for myself. If you’ve struggle with hypoglycemia and blood sugar imbalances like me, the ketogenic diet could be a great solution for reclaiming your health. What is Reactive Hypoglycemia? Reactive hypoglycemia occurs when a person experiences an abnormally high peak in blood sugar after a carbohydrate-containing meal and a subsequent steep drop in blood sugar one to three hours later, without injecting insulin. This is sometimes called “postprandial” or “spontaneous” hypoglycemia. It’s a different kind of hypoglycemia than that caused by injecting too much insulin or using other blood-sugar-lowering medications (called “iatrogenic hypoglycemia”). In reactive hypoglycemia, the body responds to a spike in blood sugar above normal levels (that is, above around 120 mg/dL) by over-producing insulin from the pancreas, or producing insulin too late. This causes a sudden drop below a healthy level one to three hours later. Hypoglycemia is generally defined as having less that 70 mg/dL of a sugar called glucose circulating in the blood, though symptoms can occur at levels higher or lower than this. A sudden crash in blood sugar can cause jitters, light-headedness, strong thirst or hunger, confusion, anxiety, weakness, sweating, and if severe enough, unconsciousness, coma, or death. Reactive hypoglycemia is a common occurrence in people with type 2 diabetes, cystic fibrosis-related diabetes, metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, or generalized “hypoglycemia”. It rarely happens in type 1 diabetes, because in type 1 the endocrine pancreas is unable to produce any insulin at all. Unfortunately, reactive hypoglycemia is poorly studied or understood, and conventional treatment methods are often unsuccessful. My Journey with Blood Sugar Dysregulation For over fifteen years I’ve been struggling with reactive hypoglycemia, a complication of my genetic disease, cystic fibrosis. Over the years it had slowly worsened, especially after I was diagnosed with diabetes in 2013. In the beginning, I only experienced hypoglycemic crashes mid-morning, one or two hours after eating breakfast. I noticed that I was especially likely to crash if I ate sugary or high-carb breakfasts, so I gradually reduced the amount of carbohydrates I ate in the morning to prevent my blood glucose from spiking. Around 2017, I started a low-carbohydrate version of the Paleo diet, keeping daily carbohydrates under about 80g. This was effective for a while, but I was also pretty loosey-goosey with it and continued to experience both hyperglycemia and hypoglycemic attacks every few days. Then, in early 2020, my reactive hypoglycemia became uncontrollable after a medication change. I was experiencing crashes daily, sometimes three or four times a day. These crashes could get critically low (as low as 30 mg/dL). I started using a continuous glucose monitor (CGM), but my blood sugar was so unstable that the CGM was not reading accurately, and so I had to finger-stick test with a glucometer around ten times per day. I especially worried about having a critical low (that is, below 55 mg/dL) while asleep… and never waking up. I literally feared for my life every day. This whole situation gave me constant anxiety and insomnia. I dove deep into the scientific literature on the endocrine system and started experimenting. As a nutritionist and clinical herbalist, I used every tool I knew of to help me balance my blood sugar. Some of it helped a little, but none of it was enough to stop the crashes from happening. Worst of all, when I experienced a crash I would often over-correct with more carbs than I needed, which would set up the next crash a few hours later. It was a terrifying rollercoaster, and I couldn’t get off the ride. In October of 2020, I was coming to my wits end. My doctors couldn’t help me. They’d just tell me to inject more insulin with meals, and then ignore me (or shrug) when I told them that would only make my crashes worse. It was at this moment that I finally decided to try what I considered to be the option of last resort: the ketogenic diet. Two and a half years later, I’m still keto and my blood sugar is more stable than ever. My chronic anxiety is gone, I can sleep through the night without concern, and I can exercise without having to stop and eat half-way through. My hemoglobin A1c has also significantly improved, from its peak at 6.5% in 2013 down to 5.1% in January 2023. I no longer use insulin at all – my blood sugar is entirely controlled by diet and exercise. This last part is unique to my particular case, as my pancreas still produces its own insulin (however improperly). Some people with blood sugar imbalances or diabetes will need to use insulin or other medications for the rest of their lives, even if they use a keto diet, and that’s perfectly ok. The goal is not to be insulin- or medication-free – the goal is to have steady blood sugar so that we can stay safe, feel healthy, and get on with the rest of our lives. What Causes Reactive Hypoglycemia? Reactive hypoglycemia can be understood as a mismatch between the amount of insulin produced by the pancreas and the amount of glucose circulating in the blood. Insulin is a hormone that the pancreas produces to move glucose out of the blood and into the tissues, where it’s used as energy for cellular activity. Normally, when we eat, the body immediately detects how much carbohydrate we ingested and produces the exact right amount of insulin on-demand. The pancreas also produces a small amount of basal insulin throughout the day unassociated with meals. For people with blood sugar disorders, several things can contribute to hypoglycemia. The pancreas might produce roughly the right amount of insulin, but the release might be delayed. A delay would mean that by the time the insulin begins to push the glucose out of the bloodstream, small amounts of basal insulin or physical activity might have reduced the blood sugar already, so that when the insulin kicks in, it overshoots the body’s need, eventually causing a drop below 70 mg/dL. In addition, the body may be unable to properly detect how much carbohydrate was just eaten, preventing the pancreas from judging the right amount of insulin to produce [1,2,3]. People with healthy endocrine systems might also experience occasional, non-critical hypoglycemia, but it is usually transient and self-correcting, even without food. The pancreatic hormone glucagon acts as a counter-balance to insulin, so if hypoglycemia does occur, the pancreas releases glucagon which raises the blood sugar back to healthy levels. In some people with blood sugar disorders, the pancreas does not produce glucagon properly. Failed release of glucagon occurs in reactive hypoglycemia, so the only way to correct it is to eat carbohydrates or inject exogenous glucagon. There may be other causes to hypoglycemia unique to certain disorders or diseases including insulin resistance, pancreatic tumors, liver disease, and so on. The suitability of the ketogenic diet must be judged on a case by case basis according to one’s individual diagnoses and symptoms, ideally in consultation with a knowledgeable healthcare practitioner. Why Choose Keto for Addressing Hypoglycemia? The primary reason keto is a great choice for those of us with blood sugar imbalances is that by eating fewer carbohydrates we prevent spikes in blood sugar, minimize insulin secretion, and prevent post-meal crashes. Reducing insulin secretion helps us avoid an insulin overshoot and excessive drop in blood sugar. By reducing carbohydrate intake to a total of around 20-60 grams per day (tailored to one’s individual needs) our tissues learn how to gain energy from ketones rather than glucose. Ketones are small molecules produced by the liver from the breakdown of fats. Ketones are normally produced during fasting and other times when dietary carbohydrates are unavailable. Ketosis is a physiological state in which the body produces and is fueled primarily by ketones. Nutritional ketosis is a natural adaptation which allows for metabolic flexibility when food sources shift or become scarce. In fact, ketones are the preferred fuel of the vital organs such as the kidneys, heart, and brain. Studies have shown that nutritional ketosis can improve many neurological conditions including epilepsy, Parkinson’s, migraines, Alzheimer’s , and depression [4]. The transition to ketosis doesn’t happen overnight. The conversion can take weeks or months, depending on the individual’s physiology and how strictly they adhere to the diet. Not everyone needs to monitor their ketone levels with urine strips or a blood ketone meter, but for those of us with unstable blood sugar, it may be a good idea to do so. This can help us know if our diets are adequately producing enough ketones to keep the blood sugar steady. I aim for a blood ketone level of 1.0 to 2.0 mmol/L, though I don’t test every day. Being in ketosis means that I can eat less frequently and am hungry less often, but I don’t usually skimp on calories. Even though I rarely have crashes anymore, I still keep a little tube of maple sugar cubes with me when I exercise, just in case. I’ve discovered that a half-cube (amounting to about 3g of sugar) is enough to rescue me from most hypoglycemic episodes. Sometimes, if I poorly time post-meal exercise, I can slide into a mild hypoglycemia which is easy to correct with a small amount of maple sugar. Another benefit of ketosis is that it’s inherently anti-inflammatory [5]. Paired with a whole foods diet including low-carb vegetables, grass-fed and pasture-raised animal products, and small amounts of nuts, the keto diet is a great choice for reducing systemic inflammation, which in turn improves insulin resistance. Getting Started We’re using the ketogenic diet as a therapeutic medical intervention, therefore it’s important to approach it with caution and adequate planning. Do your research before starting (see resources listed below). Inform your medical practitioners you’ll be trying something new with your diet, and develop ways to track your progress and record what works and what doesn’t. I’ll be honest with you, the beginning can be a little tough, most especially because it requires some experimentation as you learn more about your body’s particular needs. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to going keto, but I can offer some tips based on my own mistakes and successes:

Not ready yet to commit to keto? For those not yet ready to commit to the keto diet, it may be good to spend some time doing research and practicing a few of the tips I outline above. In particular, I think tips number five, six, ten, and eleven are the most important for anyone wanting better blood sugar control. These steps will help even if you’re not following a strict low-carb diet. Experimenting with these steps first can help build the willpower needed to start and stick with a keto diet. In addition, I recommend paying attention to your stress level. Both physical and psychological stress release cortisol, a stress hormone which contributes to insulin resistance and unstable blood sugar. Mindfulness, deep breathing, rest, and good sleep hygiene are very important for blood glucose regulation. Also consider cutting out sugar and experimenting with using a low-carb sweetener like whole-leaf stevia powder. Read up on the glycemic index and cut out refined carbs (like white flour) and other foods which spike blood sugar more quickly. Lastly, cinnamon bark (as powder, tincture, capsule, tea, or added to food) has been used for thousands of years to stabilize blood sugar, and studies have shown it to be effective at slowing the rate of carbohydrate absorption and improving insulin sensitivity. I hope this article has been helpful for you to understand more about why reactive hypoglycemia happens and what steps you can take to address it. There are many great resources out there to learn more about ketosis and the keto diet. Here’s a video introduction to the ketogenic diet by Dr. Dominic D’Agostino. He runs a helpful website with lots of scientific information and tips on the keto diet, including an excellent list of books, apps, and other resources to get started. If you’re interested in the science of ketosis, here’s a short article on its basic metabolic pathways. I’ve found Thomas DeLauer’s Youtube channel to be a rich resource of practical guidance on ketosis and intermittent fasting. I also appreciate the research of Dr. Peter Attia, an expert on ketosis who runs a great blog and podcast on the science of ketosis and fasting. There is much more to say on this topic, so if you’d like me to write about any of the above topics in greater detail, please leave a comment below. If you have used a low-carb or ketogenic diet to balance your blood sugar, please tell us about your experiences and insights! Thank you for reading. I wish you success in your healing journey. References: [1] Hicks, R., Marks, B. E., Oxman, R., & Moheet, A. (2021). Spontaneous and iatrogenic hypoglycemia in cystic fibrosis. Journal of Clinical & Translational Endocrinology, 26, 100267. [2] Battezzati, A., Mari, A., Zazzeron, L., Alicandro, G., Claut, L., Battezzati, P. M., & Colombo, C. (2011). Identification of insulin secretory defects and insulin resistance during oral glucose tolerance test in a cohort of cystic fibrosis patients. European journal of endocrinology, 165(1), 69. [3] Kandaswamy, L., Raghavan, R., & Pappachan, J. M. (2016). Spontaneous hypoglycemia: diagnostic evaluation and management. Endocrine, 53(1), 47-57. [4] McDonald, T. J., & Cervenka, M. C. (2018). Ketogenic diets for adult neurological disorders. Neurotherapeutics, 15(4), 1018-1031. [5] Pinto, A., Bonucci, A., Maggi, E., Corsi, M., & Businaro, R. (2018). Anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of ketogenic diet: new perspectives for neuroprotection in Alzheimer’s disease. Antioxidants, 7(5), 63.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Author

Mica (they/he) is a clinical herbalist, nutritionist, researcher, and writer living in Abenaki territory (Vermont). *************************** Disclaimer: The content of this website and blog is for educational purposes only and should not be considered medical advice. The information provided here is not intended to replace medical care. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Photo from BotanikGuide

RSS Feed

RSS Feed